- Home

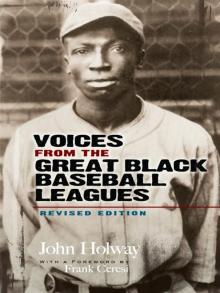

- John Holway

Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues

Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 1975, 1992, 2010 by John Holway

Foreword Copyright © 2010 by Frank Ceresi

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2010, is an unabridged, slightly emended republication of the 1992 revised edition of the work published by Da Capo Press, Inc., New York. The book was originially published by the author in New York in 1975. Frank Ceresi has provided a new Foreword to the Dover edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Holway, John

Voices from the great Black baseball leagues/John Holway; foreword by Frank Ceresi.

Rev. ed., Dover ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

9780486136479

1. African American Baseball players—Biography. 2. Negro leagues—History. I. Title.

GV865.A1H615 2010

796.3570922—dc22

[B]

2009041620

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

47541701

www.doverpublications.com

To My fellow authors,

the blackball stars

I wish to thank Ric Roberts and Merl Kleinknecht of the American Society for Baseball Research for their enthusiastic help. Mr. Roberts, a long-time sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Courier, provided incomparable insight into the lives and times of the black ball stars. Mr. Kleinknecht, like myself a recent explorer in this uncharted landscape, compiled the lifetime playing records of these and many other veterans of those days. Cliff Kachline, historian at the National Baseball Library at Coopers-town, assiduously collected biographical data on all the players and began the impressive job of adding exhibits of the old Negro leagues to the museum at the Hall of Fame. I also wish to thank my fellow author, Ocania Chalk, for generously sharing his photographs with me.

History is a myth agreed upon.

—NAPOLEON

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

FOREWORD TO THE DOVER EDITION

PREFACE TO THE 1992 EDITION

Introduction: The Invisible Men

Chapter 1 - THE MAJOR LEAGUE NOBODY KNOWS

Chapter 2 - BILL DRAKE

Chapter 3 - DAVID MALARCHER

Chapter 4 - CRUSH HOLLOWAY

Chapter 5 - WEBSTER McDONALD

Chapter 6 - NEWT ALLEN

Chapter 7 - COOL PAPA BELL

Chapter 8 - TED PAGE

Chapter 9 - TED “DOUBLE DUTY” RADCLIFFE

Chapter 10 - BILL FOSTER

Chapter 11 - LARRY BROWN

Chapter 12 - WILLIE WELLS

Chapter 13 - WILLIAM “SUG” CORNELIUS

Chapter 14 - BUCK LEONARD

Chapter 15 - HILTON SMITH

Chapter 16 - JAMES “JOE” GREENE

Chapter 17 - MRS. EFFA MANLEY

Chapter 18 - TOM “PEE WEE” BUTTS

Chapter 19 - OTHELLO RENFROE

Sunset Before Dawn

APPENDIX - Lifetime Statistics

INDEX

A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST

FOREWORD TO THE DOVER EDITION

It was a couple of decades ago that I began to develop an interest in, and later a passion for, the circuit that today we call simply “the Negro Leagues.” My journey into that slice of Americana blossomed slowly, in fits and starts, when I learned some fascinating tidbits from various sources over the span of several years. Being a typical baby boomer baseball fan, by the time I was in my mid teens I was vaguely acquainted with the names of legendary black players like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson. But my knowledge of black baseball stars who did not play in the major leagues pretty much ended with those two. And information about Satch and Josh was, in my world, sketchy at best.

I knew Paige was supposed to have been quite a pitcher and a colorful character to boot. It seemed that any discussion about him revolved around his “real age.” In fact, my college dorm room wall even featured a yellowed copy of Paige’s six “rules of life,” my favorite being rule number four, which I totally ignored at the time, but which read: “Go very lightly on the social vices such as carrying on in society, the social ramble ain’t restful.” Anyway, Paige’s counterpart was the fearsome looking but smiling Josh Gibson. He was much more mysterious. I knew that someone had dubbed him “the black Babe Ruth,” and I also learned that during the war years Gibson had played at Griffith Stadium right in my hometown of Washington D.C. Somewhere I picked up that he played for a ball club that I—a typical kid who knew every major league statistic before I knew how to balance a checkbook—had never heard of before, a team called the Homestead Grays.

Huh? What league were they in?

But Paige plied his trade on the mound and Josh’s big bat graced the Gray’s lineup long before Jackie Robinson cracked the color barrier in 1947. And, just as important, long before television came into each of our living rooms (that box brought the game to my generation). Also, critically, the Topps baseball cards of my youth featured exactly zero cards of Paige as a Negro Leaguer or of Gibson. Nor, in fact, did the cards show any member of any team from the so-called “Negro Leagues” (those Topps cards were, after all, my generation’s currency).

So how was I supposed to know that Paige threw far more no hitters in his professional career than Walter Johnson, Bob Feller and Sandy Koufax combined? Or that Gibson’s Grays, featuring top flight players across the board, won eight Championships over the span of nine years while playing in my hometown and were perhaps the greatest team of professional ballplayers ever assembled?

I would not learn those interesting morsels for another couple of decades.

In 1966, during his own Hall of Fame induction speech, Ted Williams, my favorite player then and now, told me (and anyone else willing to listen) that there were countless men who had toiled in rural ball fields all along America’s blue highways. Those men were, however, not white or Hispanic, those men were black. It was the Williams speech that first struck a chord with me, as his words hinted that something in the museum honoring our National Pastime was not quite right, or fair. Ted’s words precisely: “Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel ... I hope someday Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson will be voted into the Hall of Fame as symbols of the great Negro Players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance.”

What? There were others? You mean that Paige and Gibson actually had teammates?

So as I began life in the real world (translation: after college), I knew that something just did not add up in “my” baseball world, something was missing. What did Williams mean? Was Paige more than just a clever “ageless” man with funny retorts about life and baseball? What about this Josh Gibson, a man who had played championship ball a few miles from the United States Capitol in the very same ballpark where my woeful Washington Senators languished in last place, or close to it, year after year after year? Who were these guys who were prevented from playing in the majors simply because of the pigment of their skin? There was no mention of them either on my gum cards or in Cooperstown’s hallowed halls.

Nor were there any books on the shelf that talked of these guys. What gives?

That is when John Holway, a man who I consider a national treasure, stepped into the breach. To help answer those questions for my generation and for all those to come, he embarked upon a task that was not easy. I have since learned from John, who today is a close friend of mine, that his interest in black baseball was piqued right in my own backyard. This

was in 1945 when, as a teenager, he saw Satchel’s Kansas City Monarch’s play against Gibson and the Grays at Griffith Stadium. John tucked this childhood memory away until years later when, as an accomplished sports historian who had written the very first books in English on Japanese baseball and on sumo wrestling, he began to comb the sports pages of arcane newspapers stashed at the Library of Congress for coverage and statistics related to those who had played in that “other” league, the Negro Leagues.

Like so many others who share a passion for history and baseball, you might say that John’s curiosity got the best of him. An occasional free night or weekend at the Library turned into months and months of archiving and research. Months then turned into years. John was, after all, exploring uncharted waters. And there were not too many who had the same passion or, at the very least, the same doggedness and determination, to go forward. However, John had heard that there was at least one fellow whose interest mirrored his own. In 1970 that fellow historian, scribe and friend, Robert Peterson, had published his own extraordinary book, Only the Ball Was White. That was important. It only added to John’s thirst for knowledge. So he forged ahead.

John learned that African Americans had been playing “America’s Game” for as long as whites, but that mainstream newspapers rarely, if ever, actually reported upon and covered the black ballplayers and their teams. This might have been an impediment for some, but for John it was an opportunity. Why not hear, John thought, about the game from the player’s themselves? Certainly some must be alive and perhaps they would be willing to share their stories. So John took it upon himself, at his own expense, to travel across the country to interview many of the very ballplayers who had plied their trade in the years before Robinson’s historic debut in 1947. Over the span of several years, John interviewed well over a hundred Negro Leaguers, preserving from each their own unique and colorful stories.

Let John tell us what happened. “One of the first men I was referred to was (Buck) Leonard in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. I grabbed a tape recorder and my two sons and drove down there. Buck referred me to “Cool Papa” Bell in St. Louis and Hilton Smith in Kansas City ... from there the trial fanned out.” And the stories, ripe for the telling, kept coming. Soon words and recollections, reminiscences and memories, were tumbling out of the mouths of a proud group of men. Over time John would come to realize that it was precisely these stories that gave the Negro Leagues the color and substance that continues to give life to the players and their joys and struggles.

Eventually, by piecing together bits and pieces of information culled from his copious research notes and interviews, John published a series of six books dedicated exclusively to the Negro Leagues. And, God willing, there are more to come! He has also written a fantastic screenplay, Kick Mule, which is ripe for the right filmmaker. What you are holding in your hands is the very first book of the series, the influential and classic Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues. Thirty-five years ago, this wonderful book introduced us all to the exploits on and off the diamond of great baseball players, many of who were virtually unknown at the time. Today their ranks include no less than five Hall of Famers—“Cool Papa” Bell, Buck Leonard, Bill Foster, Willie Wells and Effa Manley, the only woman so honored. If you have never read the book, I envy you, for you are about to enjoy a rare treat. For those of you (like me) who did read it many years ago, I invite you to once again savor the stories of the greats who played our National Pastime the way it was supposed to be played, simply for the love of it.

Frank Ceresi

Frank is an attorney who has enjoyed baseball his entire life. He has written numerous articles about the history of the National Pastime (see www.fcassociates.com) and has co-authored Images of America: Baseball in Washington D. C. (Arcadia Publishing 2002) and Baseball Americana: Treasures at the Library of Congress (Harper Collins, 2009). He is currently working on a book about Bob Feller and another on baseball in Cuba. Ceresi has known John Holway, one of his writing heroes, for over a decade.

PREFACE TO THE 1992 EDITION

Once an uncharted moonscape, the landscape of Negro League baseball is now much better mapped.

Little Willie Wells was considered a slap hitter. But now we have proof that he’s the Roger Maris of the Negro Leagues. No Negro Leaguer hit more home runs than his 27 in 1929.

Bill Foster’s lifetime records may be found in the Macmillan Encyclopedia, 1990 edition, along with the statistics on most of the men found in this book, thanks to the labor of love of many researchers who devoted thousands of hours to searching the newspaper record and compiling the data.

The scholarship will go on—more box scores will be found, and the numbers updated or corrected.

Of the 18 persons herein who told their tales into my tape recorder, 16 have passed on. But the stories they left behind will go on. They have enriched the history of baseball—and our country—by recalling to life the heroes and the days now gone. Through them we can dial up on some celestial VCR the games and the lives of yesteryear.

And now, with this new edition, a younger generation of fans can read them and enjoy meeting the men who made the history.

–JOHN B HOLWAY

Alexandria, VA

October 1991

PUBLISHER’S NOTE:

Since Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues was originally published in 1975, hundreds of statistics covering the careers of the men in this book have been uncovered. These statistics may be found in an appendix beginning on page 355.

Introduction: The Invisible Men

As I look back on my career—and it was wonderful to me, and I’m thankful that I was given the chance to play baseball; it’s about the only thing I could do —and I’ve thought many a time, what would have happened to me if I hadn’t had a chance to play baseball? A chill goes up my back when I think I might have been denied this if I had been black.

—TED WILLIAMS, accepting a brotherhood award at Howard University, 1971

The first time I saw Josh Gibson was on a humid Tuesday night in May of 1945 in the old, green-painted, ad-studded but intimate confines of Washington’s Griffith Stadium. I was fourteen then. The park was a long ride by bus from my home in Alexandria to Washington, where we changed from the segregated Virginia bus—whites in front, blacks in back—and boarded the integrated Washington trolley. The stadium, long since fallen under the wrecker’s ball, seemed a long ride from downtown then. Today the site is deep inside “the inner city.”

Gibson was wearing the pin-stripe uniform of the old Homestead Grays, who were then working on their eighth of nine straight pennants in the Negro National League. Their bitter rivals, the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League, were in town for an interleague game, and the great Satchel Paige himself would pitch the first two innings, as he generally did, to draw a crowd.

And it was a crowd. The white paper, the Washington Post, had devoted two paragraphs to the game, more than its usual ration of news about the Grays, since, after all, Paige was in town. But the park was swarming with black fans, and every now and then a pink face or two, out to watch these two greatest players in black baseball, Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige, renew their long-standing warfare.

I remember crowding against the railing beside the Monarchs’ dugout with a swarm of scorecard-waving kids to watch Satchel warm up, his big windmill windup reminiscent of Joe E. Brown in Elmer the Great. Across the field Gibson, warming up his own pitcher, looked round-faced and cheery, a beardless black Santa throwing his head back and chuckling at a dozen things that had touched his funny bone.

Josh didn’t hit any home runs that night. And that’s all I remember about the game, frankly. I’m not even sure what the score was, although I think the Monarchs won. The only other player I knew by name was the Grays’ hard-hitting first baseman, Buck Leonard, sometimes dubbed “the black Lou Gehrig.” The rest of the names were a blank to me.

Did Cool Papa Bell roam center field for the Grays?

Did he steal a base that night? Did Hilton Smith come in to relieve Satchel and sew the game up as he had done for so many years? Did the veteran Newt Allen cavort at second base for the Monarchs?

Later these men became friends of mine. But that night I looked right at them and didn’t even see them. Their names meant nothing to me. Like most fans of that day, I considered them semipro’s, maybe AA minor leaguers at best. Otherwise, why would they get so little attention in the papers?

Six months later a Monarch rookie, Jackie Robinson, was signed by the Dodgers, the Monarchs were in town again, and I returned to see them in a Sunday doubleheader. I remember Buck Leonard hitting a fly ball high against the right field wall, close to the spot I had seen Charlie Keller of the New York Yankees reach just a few days earlier. Too bad, I thought idly, that Leonard and Keller couldn’t play on the same field so we could really compare.

Then I forgot about the subject, until some twenty-five years later, when I happened to read Satchel Paige’s book, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever. Perhaps the story of the long dead Josh Gibson would be just as fascinating, I mused. I began calling people in the Washington area who might have known Gibson. One of the first men I was referred to was Leonard, living in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. I grabbed my tape recorder and two sons and drove down there. Buck referred me to Cool Papa Bell in St. Louis and Hilton Smith in Kansas City, so on my vacation I took the boys out West for more recorded talks. From there the trail fanned out.

For what I had stumbled on by accident was a virtually unexplored continent. The world of black baseball history was not a mere footnote to baseball history—it was fully half of baseball history!

And maybe—the thought was stunning—the bigger half.

Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues

Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues